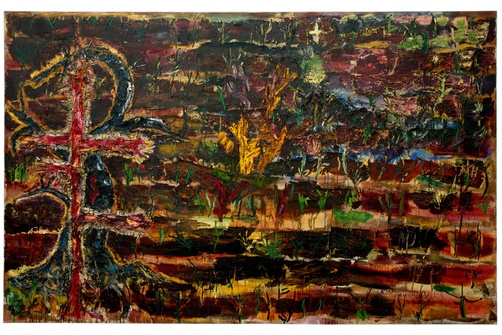

In fall 2018, Assistant Professor and Associate Chair of Dance Sarah DiPasquale connected visual art and dance in a course for Skidmore students and the Saratoga Bridges community of differently abled adults. The class examined Joan Snyder’s painting Waiting for a Miracle (for Nina and John) (1986) and, in response, developed choreography for an integrative dance, which was performed on December 10, 2018.

Sarah DiPasquale

Associate Professor and Chair of Dance

Skidmore College

The “Bridges to Skidmore” course was created in 2010 by Associate Dean of the Faculty and Professor of Social Work Crystal Dea Moore as a non-credit-bearing college experience for differently abled adults from the Saratoga Bridges community working together with Skidmore students.(1) In 2017, I redesigned the program to be a dance course and scholarly initiative examining the physical effects and creative processes of integrative dance on this population.(2) In the current course model, individuals from Saratoga Bridges are matched with Skidmore students, and together they engage in an integrative dance experience. As Caroline Kelberman ’17 and I have written, “Integrative dance may be defined as dance that encourages the participation of all individuals, regardless of ability, supporting and celebrating these differences through movement.”(3) The social aspect of dance is essential to the “Bridges to Skidmore” experience. Differently abled people are often socially isolated and identify disability-service users, staff, and family members as friends.(4) For example, people on the autism-spectrum scale commonly experience a deficit in appropriate communication, social empathy, and awareness or sensitivity to others’ emotional experiences.(5) These social insufficiencies may have impacts on the development and maintenance of social relationships, and thus, may lead to social isolation.(6) “Bridges to Skidmore” was designed to meet the needs of differently abled individuals; the structure of the class was established with a conscious objective to create a socially inclusive and integrated dance environment. Profoundly important aspects to this work are the deep and meaningful relationships that form between the participants and their college-student counterparts throughout the semester.